Everyone has a favourite colour. It has defined and shaped our early friendships on the playground— the knowing smile and the excitement on another kid’s face as we reveal our fondness for the same colour.

As adults, colours become forsaken attributes of our identity. Our preferences are seasonal and contextual. But, there’s still a shade tinting our subconscious, capturing our attention once in a while to remind us that the world wouldn’t look—or feel—the same without its conspicuous existence.

We know where colours can be found in nature and what they evoke in art and culture, but we know little about their origins—so here is a brief history of colour pigments and how they made their first appearance in our lives.

Invented in 1826, ultramarine blue—which means beyond the sea, a name given for its faraway birthplace—is derived from lapis lazuli stone. For hundreds of years, the cost of the blue gem rivalled the price of gold.

The story goes even Michelangelo couldn’t afford the precious pigment and his famous painting The Entombment was left unfinished due to the lack of resources. In 1950, a synthetic—and more accessible— version of blue was created by a Parisian paint supplier and it became known as french ultramarine.

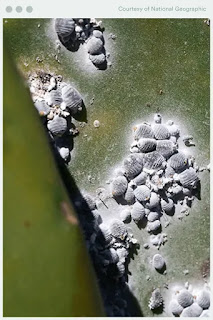

First used in prehistoric cave art, red ochre is one of the oldest pigments. In the 16th century, the most popular red pigment was extracted from a cochineal insect—a white bug living on prickly-pear cacti in Mexico, once dried and crushed, produces an intense crimson dye known as carmine. Known for its health benefits, the cochineal bug is still used to colour lipsticks and blush today.

Widely available, yellow ochre was amongst one of the first colours in existence—it was discovered in Lascaux cave art and Egyptian tombs. Decried for its excessive vibrancy, pure yellow was avoided and contemned by many artists—only a handful of painters, such as Van Gogh and Turner, dared to innovate with it thus paving the way for avant-garde movements.

For his sublime and sun-lit seascapes, Turner used the experimental watercolor. Indian Yellow—a fluorescent paint derived from the urine of mango-fed cows. This practice was banned less than a century later for its cruelty to animals, and in 1920, an artificial equivalent was manufactured and available on the market.

In ancient Egypt, realgar, a pure orange mineral, was used for ceremonial paintings—and later, repurposed to celebrate the beauty in the mundane by Impressionists. Less pure than realgar, madder roots, when heated in a vat and mixed with a mordant such as alum, created a deep orange dye.

The colour intensity of the dyed fabric faded over time through repeated exposure to sunlight and environmental elements, but if well-preserved, the brilliant orange lasted for centuries.

Despite green’s association with nature, its pigments have been some of the most poisonous and deadly in history. Green pigments have been used since Antiquity, both in the form of natural earth and malachite. Greeks introduced verdigris, one of the first artificial pigments in civilization.

In 1775, the Swedish chemist Carl Wilhelm Scheele synthesized a bright green pigment—a coppery powder laced with chemical arsenic— for commercial use. According to historians, the Scheele’s green covering wallpapers at the time may have accelerated Napoleon’s death.

By the end of the Victorian era, a similar mixture of copper and arsenic was introduced, enabling Impressionists to create their signature emerald green—which later on, was suspected to have contributed to Monet’s blindness. The green arsenic was finally banned in the 60s.

In addition to red ocher and yellow ocher, charcoal was one of the earliest pigments adopted by mankind. Vine black was produced in Roman times by burning branches of grapevines or the remains of the crushed grapes, which were collected and dried in an oven.

The first known black inks and dyes were invented by the Chinese using ground minerals such as graphite. However, for the Old Masters, all these blacks lacked durability, richness and most importantly, darkness—a unique quality imbuing paintings with depth and enigma.

Adored for its lustrous appeal and popularized as the darkest pigment ever, bone black was invented and produced by burning animal bones in an air-free chamber. The colour is still made today, however, ordinary animal bones are substituted for ivory.

Related Posts:

Comments

Post a Comment